Zenga zenga, dar dar!" ["Alley to alley, house to house."] That was the battle cry of Muammar Gaddafi and his sons when they unleashed their forces on the rebels six months ago. Now the phrase may be coming back to haunt the Gaddafis, if they are, in fact, hiding where the rebels believe they are.

Zenga zenga, dar dar!" ["Alley to alley, house to house."] That was the battle cry of Muammar Gaddafi and his sons when they unleashed their forces on the rebels six months ago. Now the phrase may be coming back to haunt the Gaddafis, if they are, in fact, hiding where the rebels believe they are.

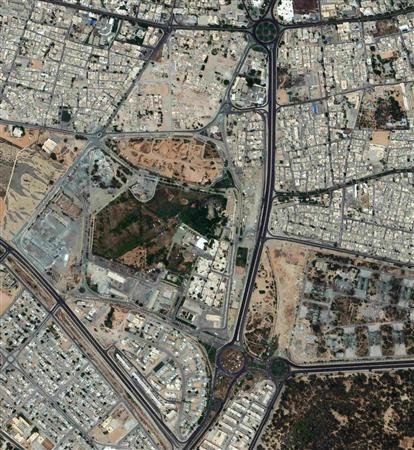

On Thursday, closing in on a string of neighborhoods in central Tripoli, rebels often moved house to house through the narrow streets of Ghabour and Abu Salim — two of Gaddafi's last known strongholds in the Libyan capital. Taking cover behind walls and concrete barricades, groups of fighters from towns across the country dodged sniper fire and waged sporadic gun battles with often invisible assailants as they hunted for the now missing Libyan dictator and his family. "The problem is, we don't know where Gaddafi is," admitted Ali al-Abbas, a Swiss-Libyan dual national at midday. "But we know that a lot of the people who escaped from Bab al-Aziziyah went to Abu Salim. And they've waged significant resistance there. So that's why we think he might be there."

Bab al-Aziziyah is Gaddafi's vast, fortified compound in central Tripoli, which in the past two days has been transformed into ripe territory for both looting and tourism by the sundry forces of the National Transitional Council, the rival of the Gaddafi regime. But the surrounding areas were long ago designed as Gaddafi defensive strongholds, the fighters say. And these streets may be where Tripoli's longest and dirtiest battle plays out — if the worst hasn't already come. "They're very aggressive," says Mohamed, a fighter who was driving out of the neighborhood at sunset, amid fierce shelling. "That means they're fighting for something."

(See pictures of the lengthy battle for Libya.)

The Bab al-Aziziyah compound — massive on its own — was militarily and logistically run from the 77 Base across the street on Airport Road. But it was the adjacent neighborhoods of Abu Salim and Ghabour that Gaddafi used to house his extensive population of staff and supporters. And the ubiquitous green flags of the regime dotting the rooftops there provide the visual reminders — amid the sniper fire — that the battle is far from over.

But there are also signs that a ferocious battle has already been fought. Thursday marked the first day that journalists were able to enter Bab al-Aziziyah Square, a grassy traffic circle in the contested part of town, set between the compound and the 77 Base on one side, and Abu Salim and Ghabour on the other. At midday rebels set fire to a sprawling, ransacked camp that had served as a makeshift supply base and field hospital for Gaddafi loyalists in recent days. The fire, some said, served to mask the stench of decaying flesh.

And indeed, on a median near the circle, nine bloated bodies lay decomposing in the harsh sunlight. A team of ambulance workers said they believed that the bodies had been there for three days while fighting overwhelmed the area.

(See photos of life in Benghazi during wartime.)

But there is strong evidence to suggest that a massacre took place there. A nearby field clinic — also part of the camp — contained more than 30 bodies. Mostly dressed in civilian clothes, they lay swollen and fly-covered, strewn over mattresses and dirt, many of them wearing bandages. Two, still on stretchers and hooked up to IVs inside a clinic tent, had been shot in the head. Another body lay on a stretcher inside an abandoned ambulance. The camp had been ransacked, with food, water bottles and medical supplies strewn about. And several of the other nine on the median had their hands bound in plastic ties behind their backs; the bullet wounds piercing their skulls, backs and chests.

The rebels say Gaddafi's forces did it. But it is still unclear why Gaddafi would have massacred the wounded at his own camp. The bodies had yet to be removed on Thursday, despite the presence of rebels in the area — the kind of treatment that Libyan rebels have typically only permitted for enemy dead. The antiregime fighters are adamant, however. "It was because they didn't like Gaddafi. So people inside the camp killed them — Gaddafi guys," says Mohanid Gomaa, 28, a fighter from Tripoli. "I live here. I saw everything," he adds.

(See a video on the mental toll of Libya's war.)

Still, the scene could pose serious new questions about Libya's future — and its new leadership's commitment to democracy and human rights — as the rebels move to consolidate control of the capital. By Thursday evening, anti-Gaddafi fighters were manning checkpoints — in some places, every 100 m — throughout large swathes of Tripoli. In Souk al-Jomaa, one of the first neighborhoods to fall over the weekend, a number of shops had reopened and children played in the street. And in Green Square, where Gaddafi had famously gathered his supporters for dramatic demonstrations in recent months, families and rebels in cars paraded around the traffic circle producing an endless cacophony of celebratory honking and gunfire.

By sunset, fierce fighting continued to wrack Abu Salim, where piles of soldiers' boots and dried pools of blood marked the remnants of the regime still lurking nearby. The rebels had begun to arrest residents suspected of being Gaddafi loyalists. Meanwhile, rumors spread that Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the colonel's favorite son and heir apparent, was cornered in a house there. It was not determined whether Saif — who the NTC had earlier incorrectly reported was in its custody — was, in fact, in the house. But trucks of fighters took turns shelling the building with just about every weapon they could find — mortars, rocket-propelled grenades and bullets in all sizes. Whoever was in the house shot back — until nightfall, when it grew quiet and it was time for everyone to break the day's Ramadan fast. At that point, the rebels pulled back

16:35

16:35

Reportage

Reportage

BENEATH the grassy courtyard of Muammar Gaddafi's compound, long tunnels connect bunkers, command centres and spiral staircases that lead to a luxurious home.

BENEATH the grassy courtyard of Muammar Gaddafi's compound, long tunnels connect bunkers, command centres and spiral staircases that lead to a luxurious home. intense battle has erupted between about 1,000 rebels surrounding two buildings filled with Moammar Gadhafi loyalists in the neighborhood next to the Libyan leader's captured compound.

intense battle has erupted between about 1,000 rebels surrounding two buildings filled with Moammar Gadhafi loyalists in the neighborhood next to the Libyan leader's captured compound. Libyan rebels said they were sending in special forces units in their hunt for fugitive strongman Muammar Gaddafi, whose supporters are now pinned down in pockets of resistance in the capital, Tripoli.

Libyan rebels said they were sending in special forces units in their hunt for fugitive strongman Muammar Gaddafi, whose supporters are now pinned down in pockets of resistance in the capital, Tripoli. More than 1,000 fighters trying to find the fallen dictator besieged an apartment in the centre of the city in the belief he was holed up inside with his sons.

More than 1,000 fighters trying to find the fallen dictator besieged an apartment in the centre of the city in the belief he was holed up inside with his sons. Muammar Gaddafi has called on Libyans to "destroy" the rebels who have overtaken Tripoli and forced his regime into hiding.

Muammar Gaddafi has called on Libyans to "destroy" the rebels who have overtaken Tripoli and forced his regime into hiding. Fighting in central Tripoli has continued - as rebels claim they have besieged a cluster of apartments where they believe Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and some of his sons are hiding.

Fighting in central Tripoli has continued - as rebels claim they have besieged a cluster of apartments where they believe Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and some of his sons are hiding. The Brother Leader is alive and remains in Libya, one senior government source said. But he added that plans are on the table to spirit him out of the country to allow breathing space for a peace process led by the National Transitional Council which has now claimed control of most of the capital Tripoli.

The Brother Leader is alive and remains in Libya, one senior government source said. But he added that plans are on the table to spirit him out of the country to allow breathing space for a peace process led by the National Transitional Council which has now claimed control of most of the capital Tripoli. Muammar Gaddafi has apparently vanished after Libyan rebels claimed to be in control of most of Tripoli following their lightning advance on the capital.

Muammar Gaddafi has apparently vanished after Libyan rebels claimed to be in control of most of Tripoli following their lightning advance on the capital.